▶ Table of Contents

A Flag Unlike Any Other

Nepali flag is the only national flag that isn’t a quadrilateral, its distinctive shape precisely defined by mathematical instructions enshrined within Nepal’s constitution.

It might look like two simple triangles joined together, but look closer. Within those crimson and deep blue borders lies a story, a careful sequence of construction, each step precise, each line a brushstroke in a grand mathematical painting.

If you Want to see these rules in action, There are tons of resources online. Numberphile beautifully demonstrated hand-drawing the flag on cardboard. It’s where I found out first that there is a rule to draw the flag. This GeoGebra project offers a step-by-step visualization using a slider. I took a picture for this article from that project. And for the coding enthusiasts, Stack Overflow has a thread where some folks generated the flag using Javascript, Python, SVG, Mathematica, and Postscript.

Here is the extracted flag construction details.

Drawing by Decree: The Geometry of Nepal’s Flag

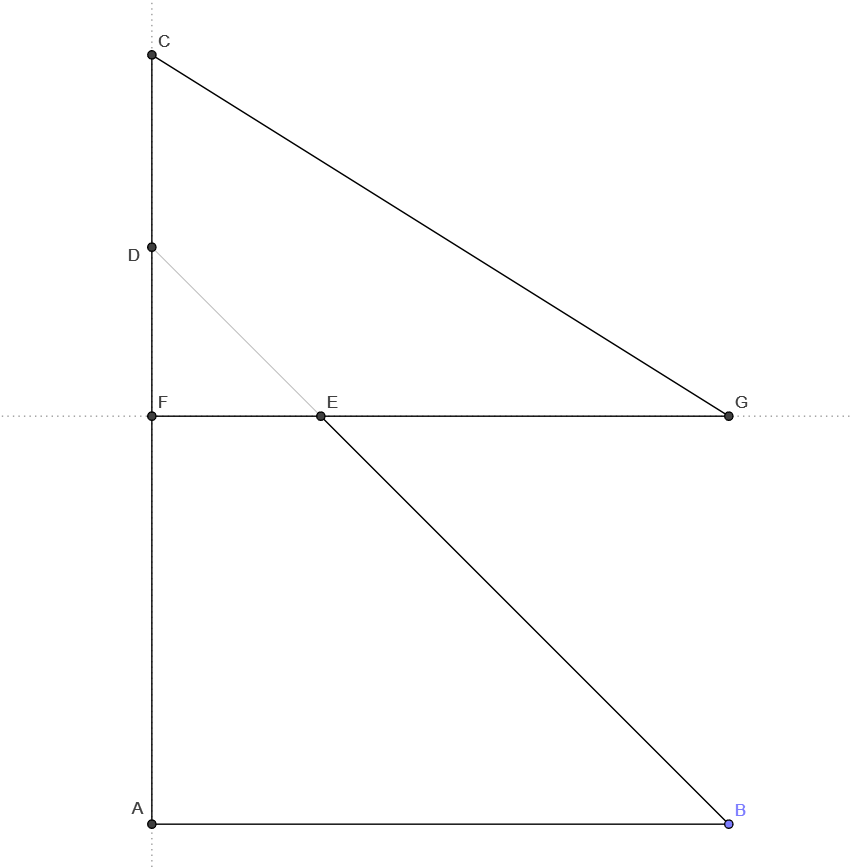

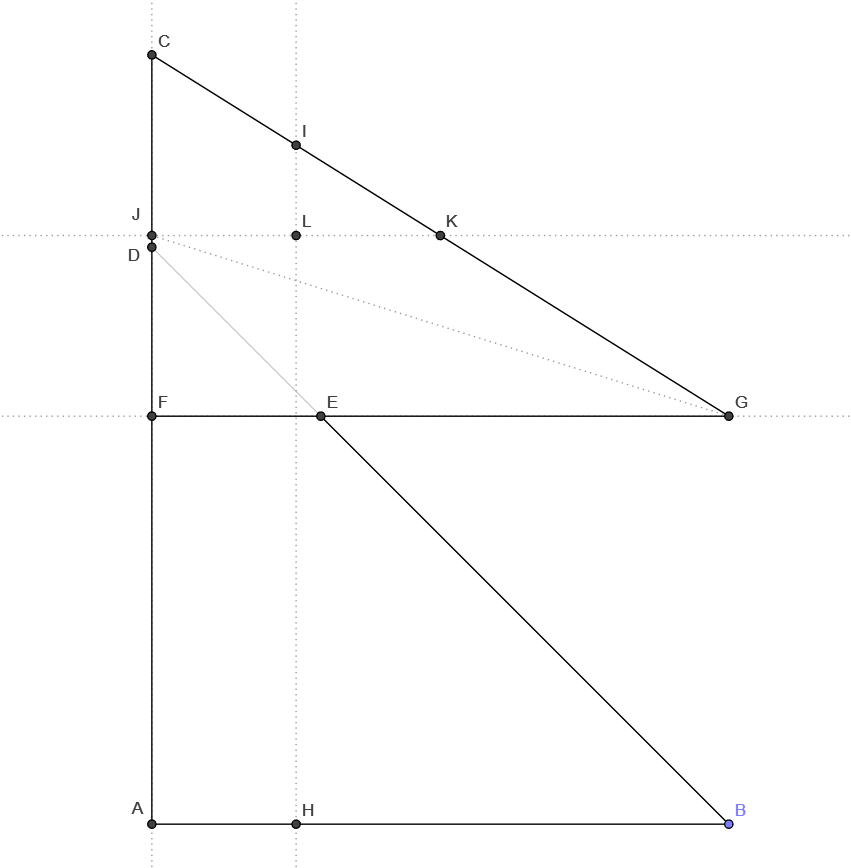

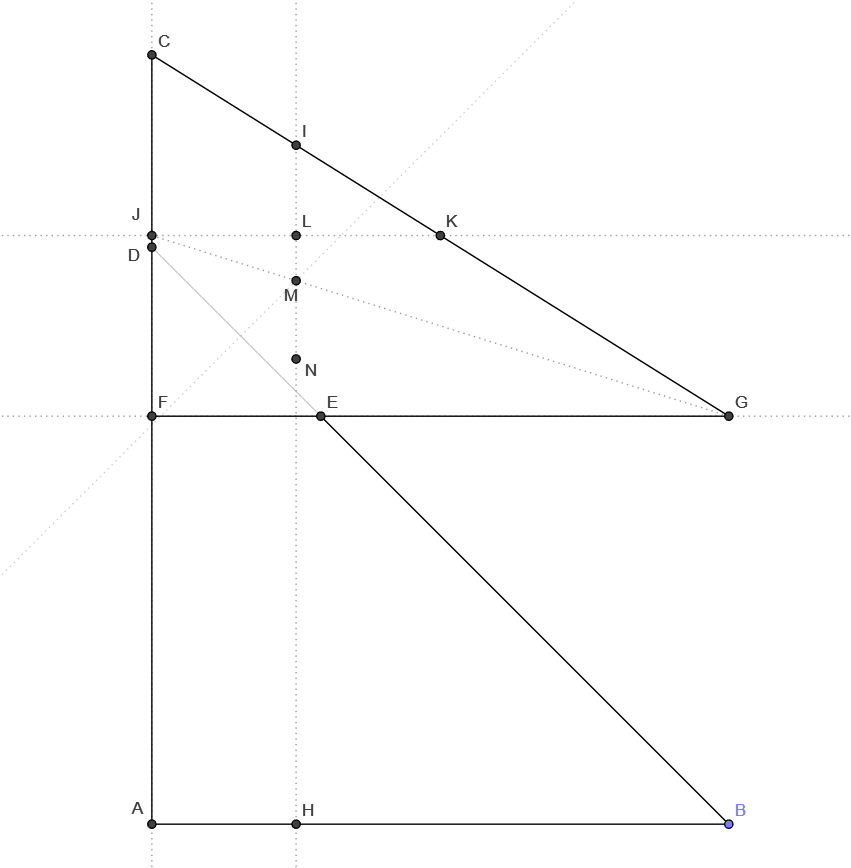

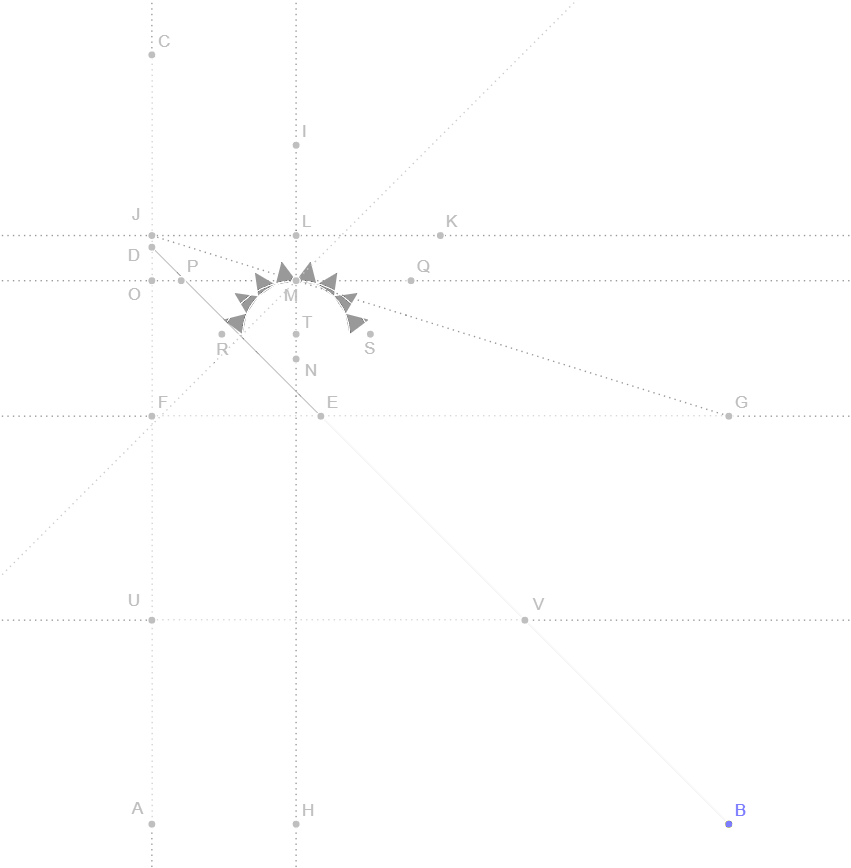

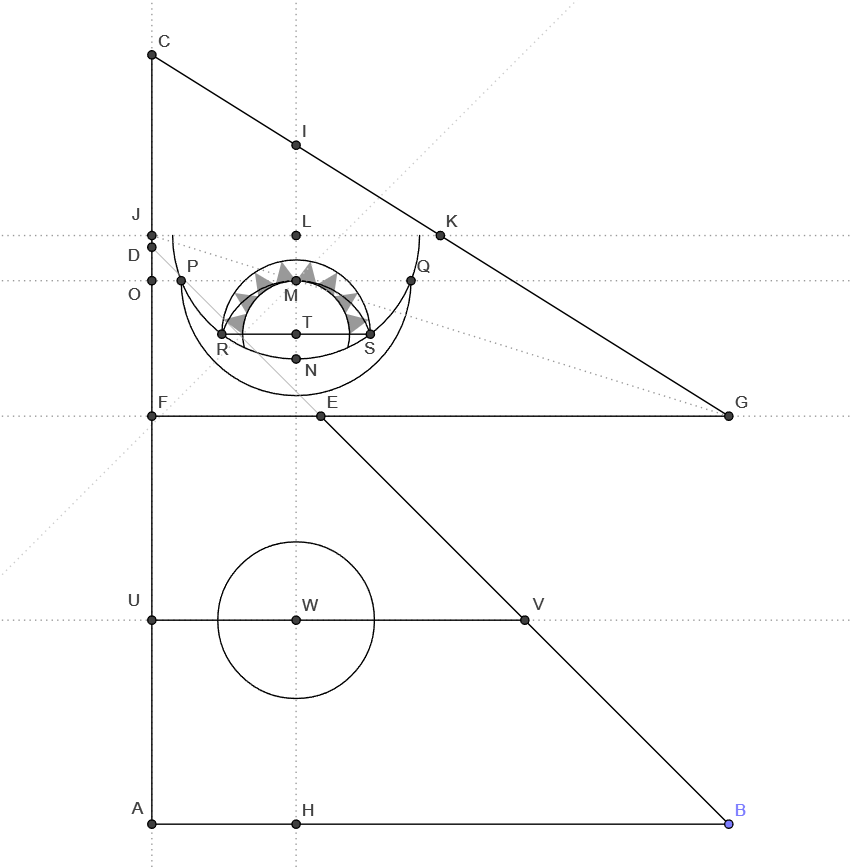

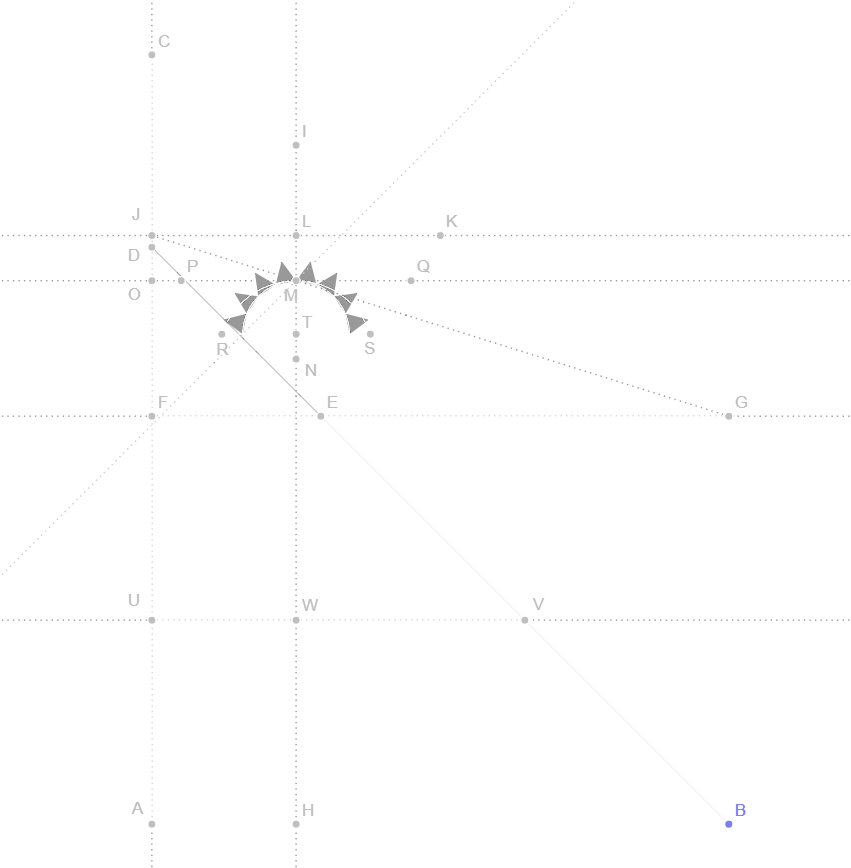

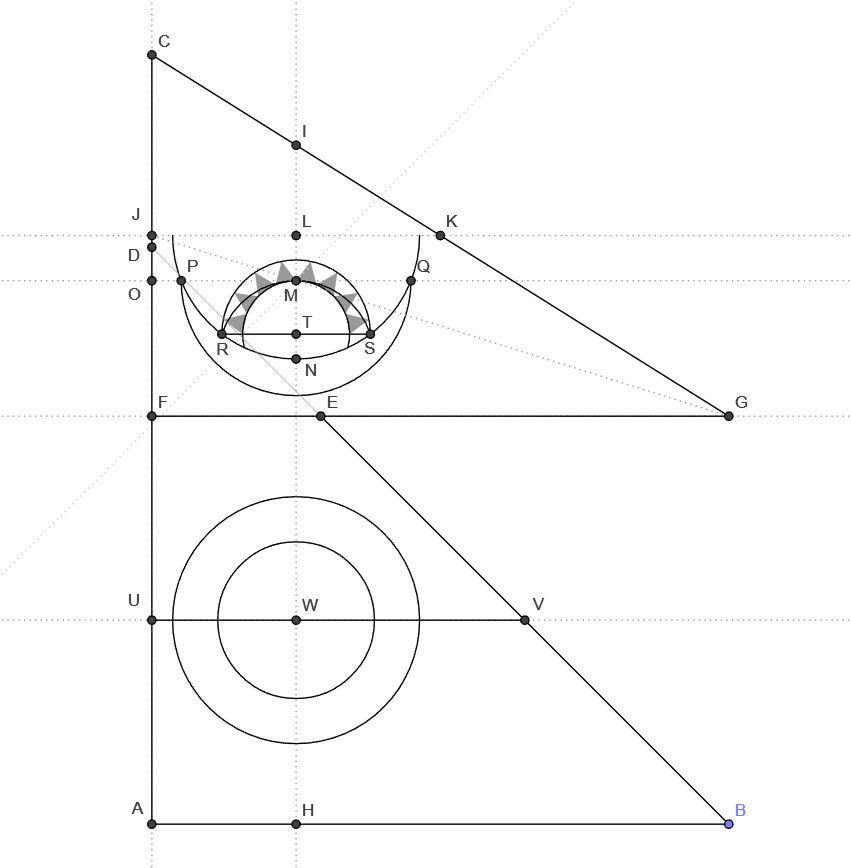

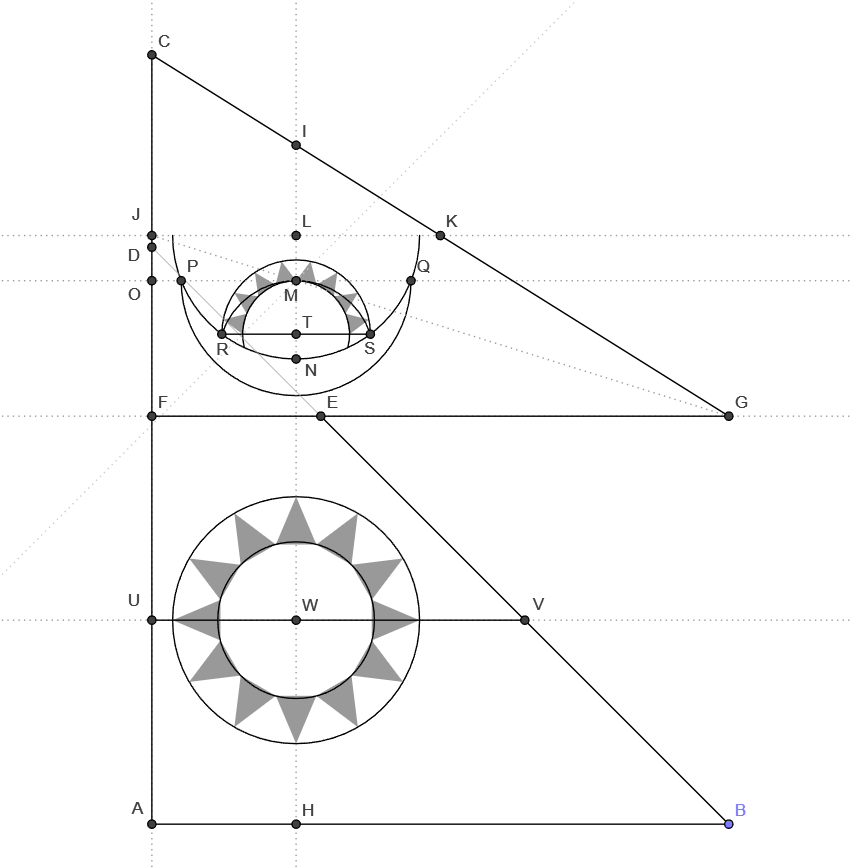

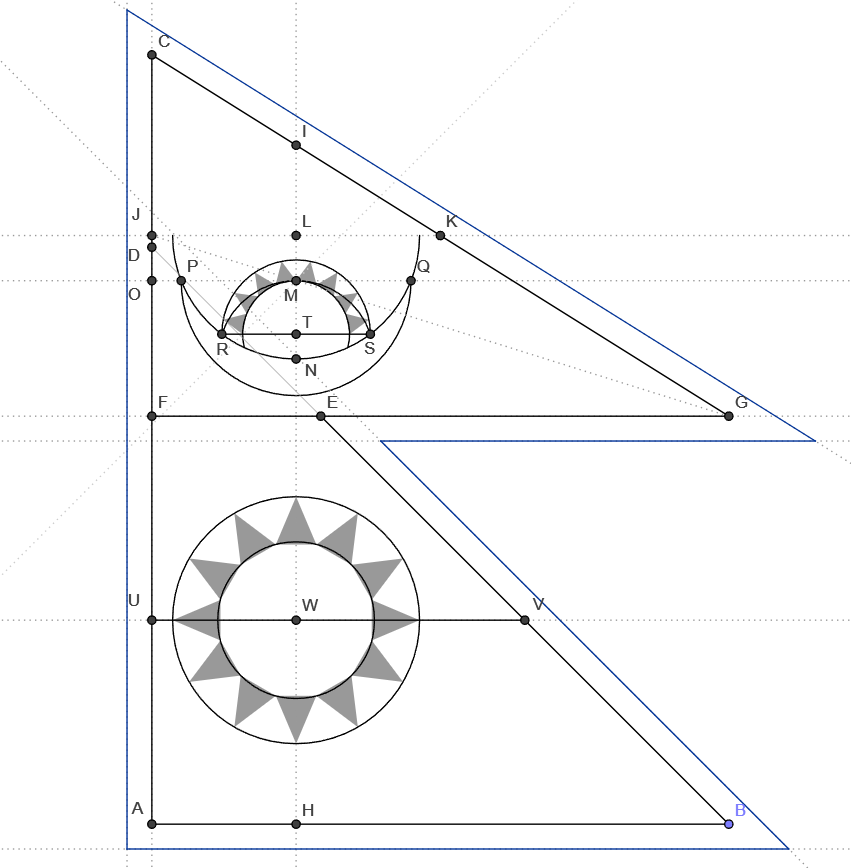

Step 1: The Foundation

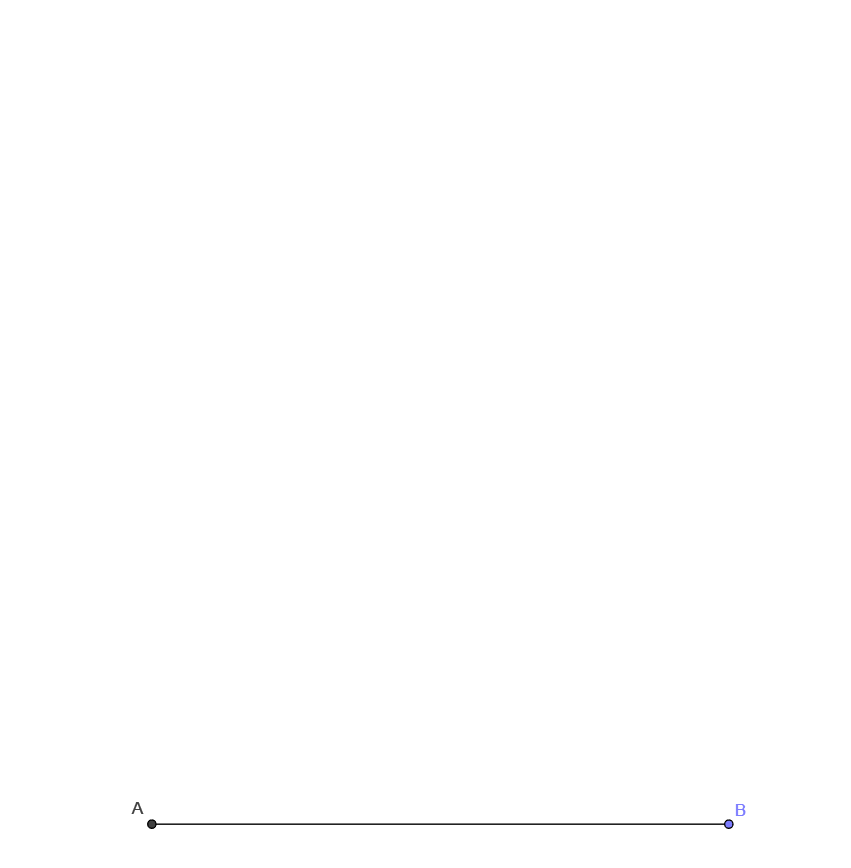

It begins with the foundation: a single line, the base.

The images I’m using come from GeoGebra, but if you’re making a real flag, you’d traditionally use crimson cloth (Hex: #DC143C, RGB: 220, 20, 60). Let’s be honest, though, printing it out is much easier!

But, if you were going the traditional route, you’d start at the bottom of your crimson cloth and draw a line, AB, any size. This line is the foundation upon which all other measurements are based, setting the scene for everything that follows.

From this foundation, the next lines will rise, forming the two distinct triangles.

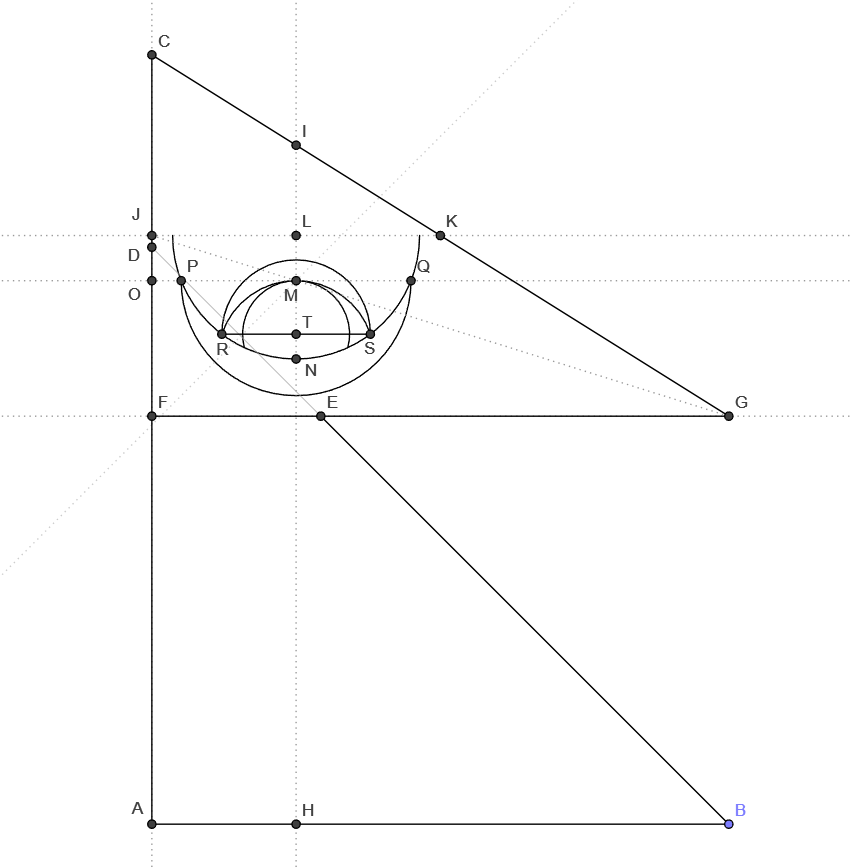

Step 2–5: Constructing the Twin Triangles

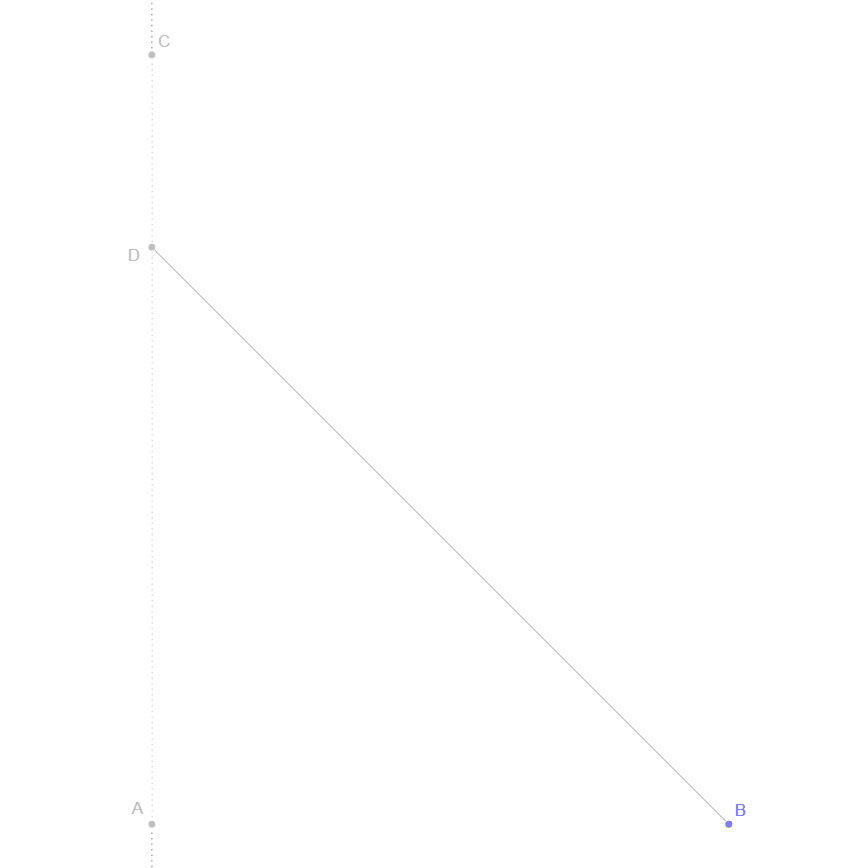

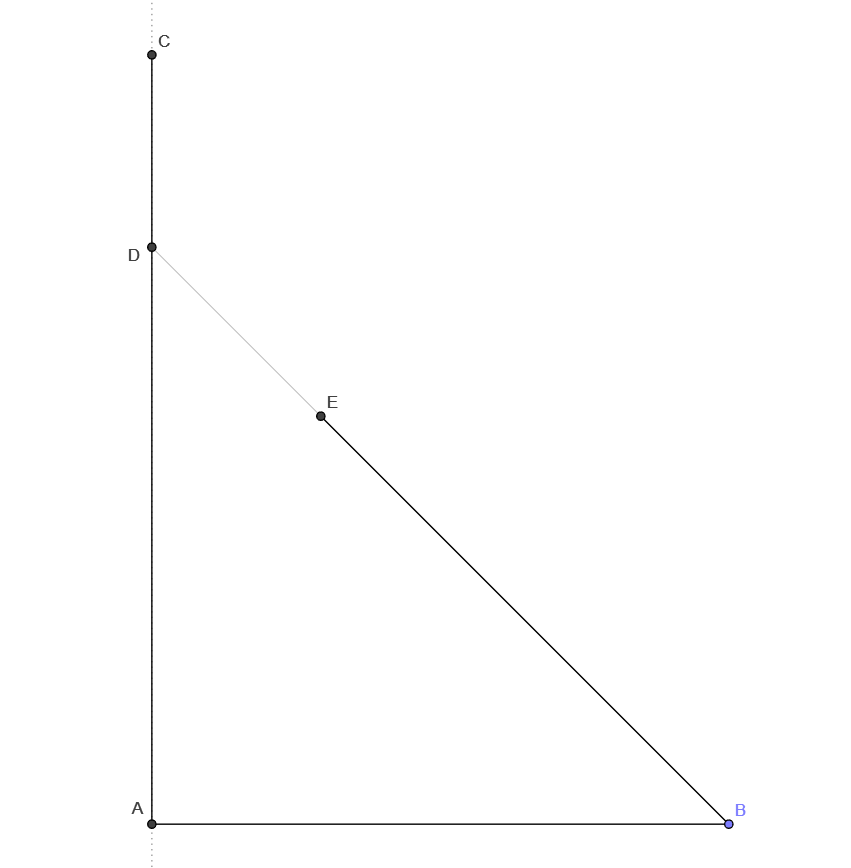

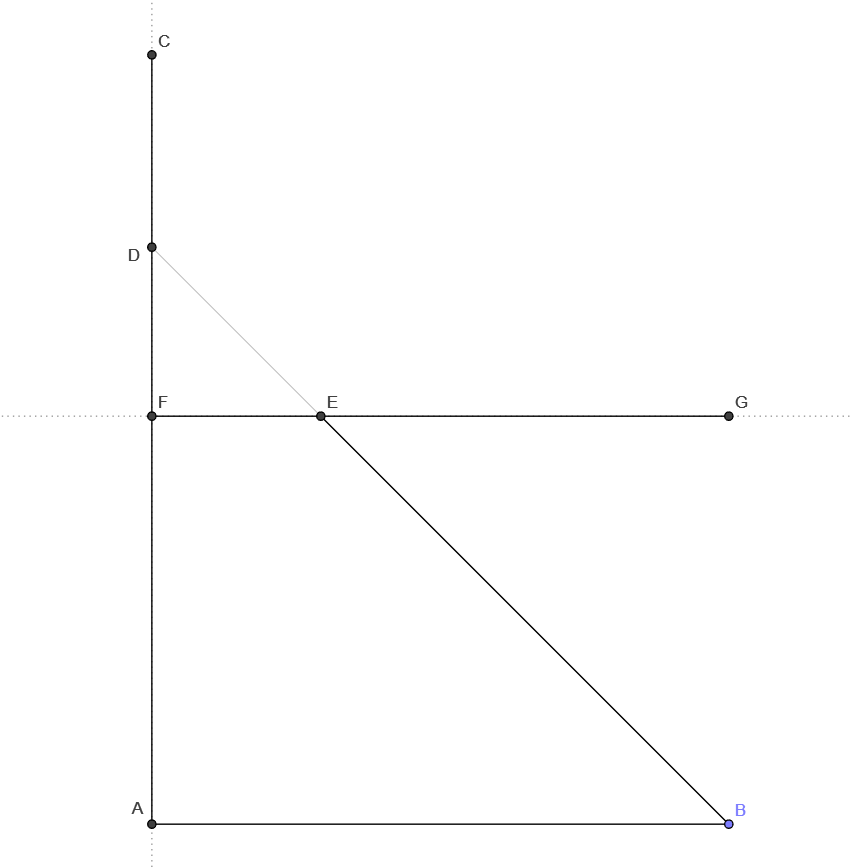

From point A, a perpendicular line AC is drawn, its length precisely determined as AB plus one-third of AB. This vertical axis becomes the backbone of the upper and lower triangles, setting the stage for their formation.

The next step is marking point D, ensuring AD equals AB, followed by connecting BD, the diagonal stroke that gives the flag its first defined shape.

The structure deepens as we bisect BD at E and extend a parallel segment FG, identical in length to AB.

With CG now established, the foundational framework is complete.

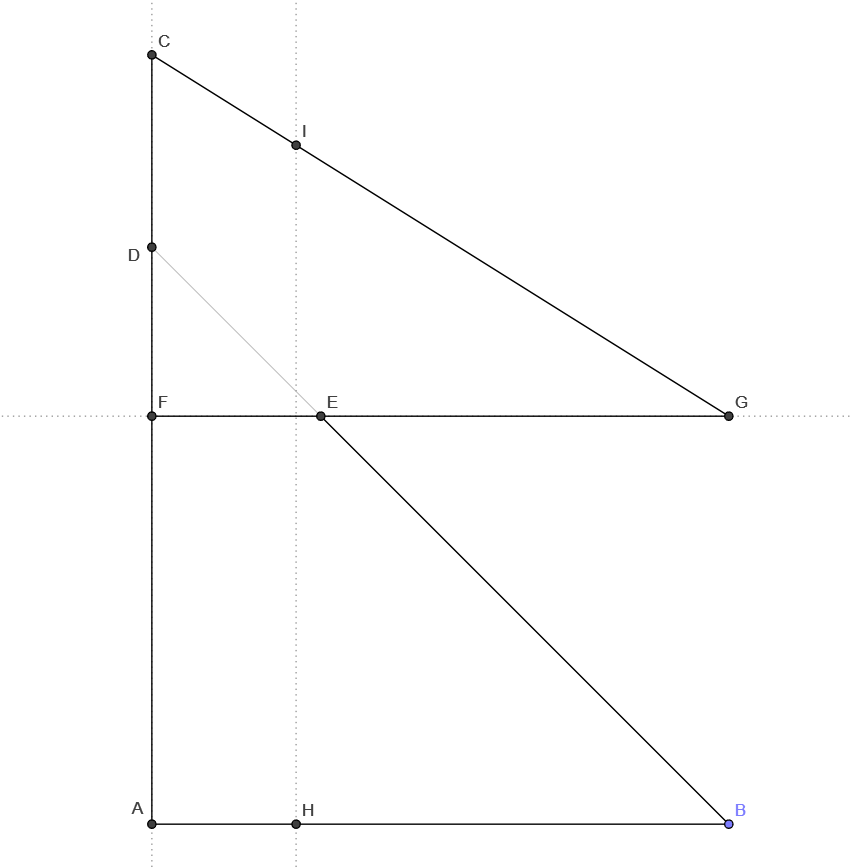

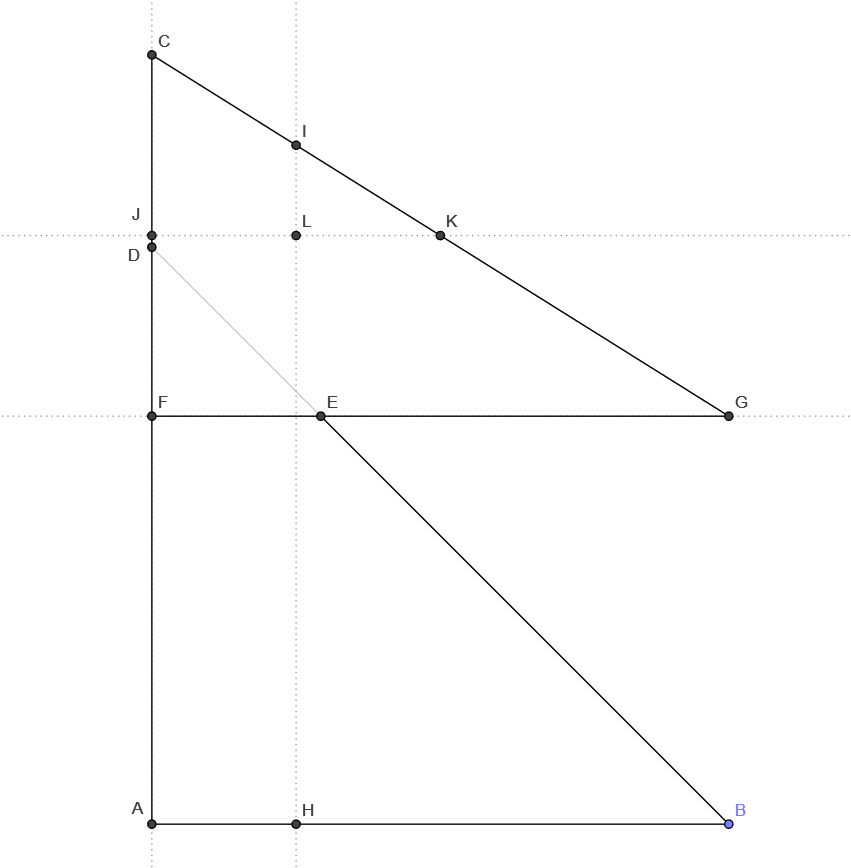

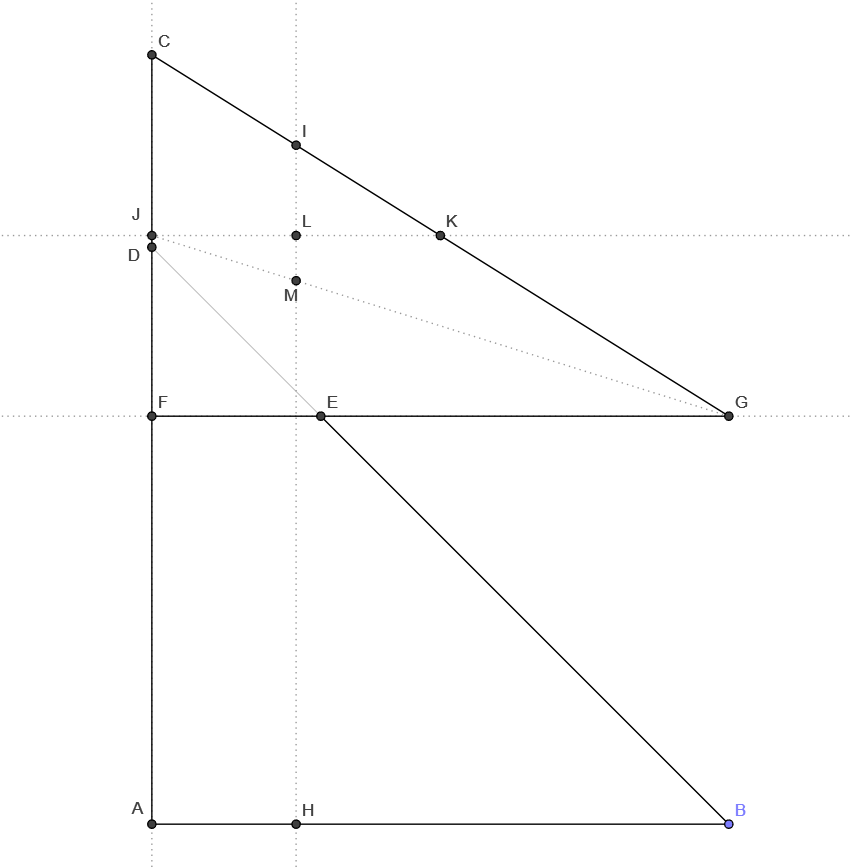

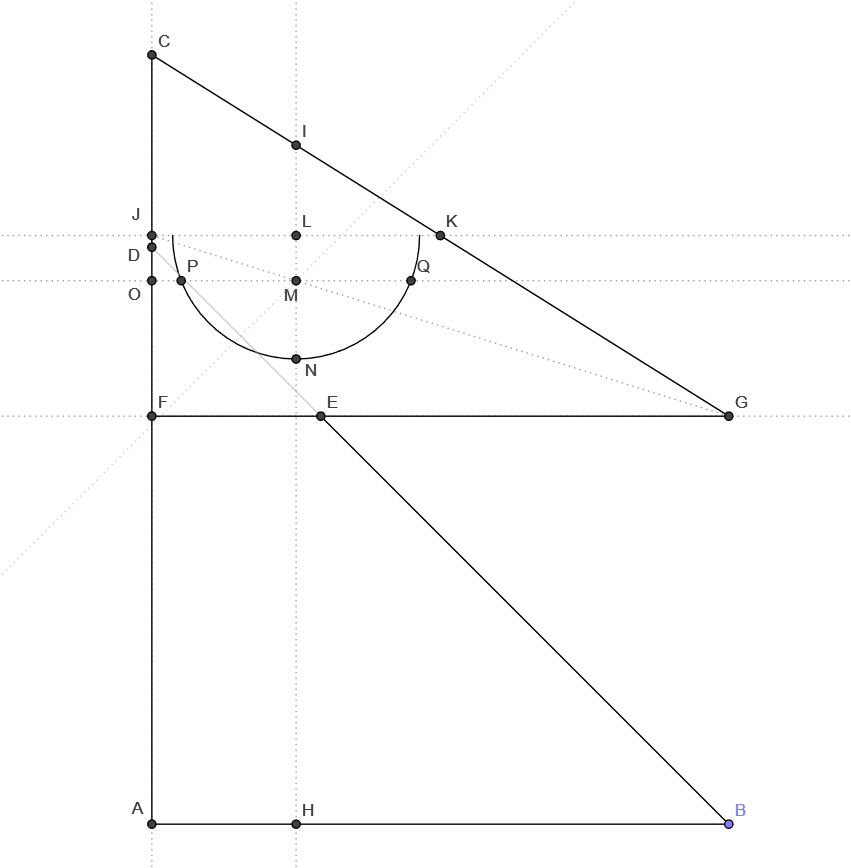

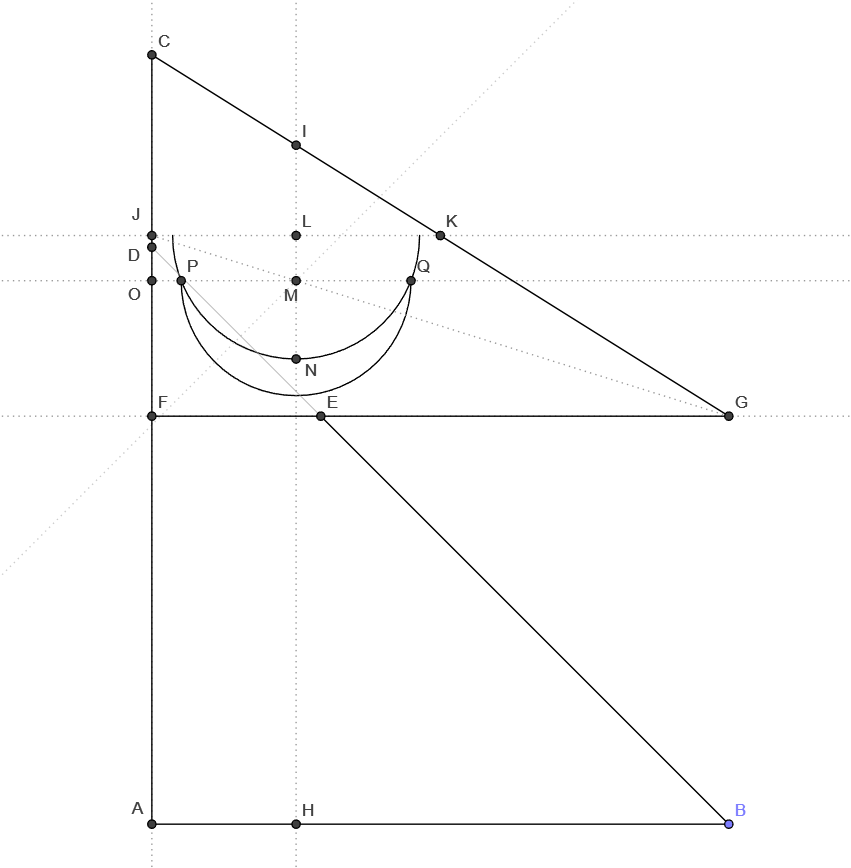

Step 6–18: Constructing the Moon

With the skeleton in place, we turn our attention to the celestial emblems, the moon and sun.

The moon, positioned on the upper triangle, is an careful assembly of arcs and radii.

From AB, we measure a quarter of its length to determine AH, establishing the moon’s placement. A vertical line HI extends parallel to AC, guiding the internal construction. Bisecting CF at J and further extending JK, we refine the structure until the central reference points emerge.

With geometric precision, arcs are drawn from centers L, M, and N, curving into crescents that form the moon’s distinct shape. Additional arcs define the eight triangular rays.

The moon takes shape as a construct of pure geometry, its curves and edges dictated by the same principles that govern the flag’s form.

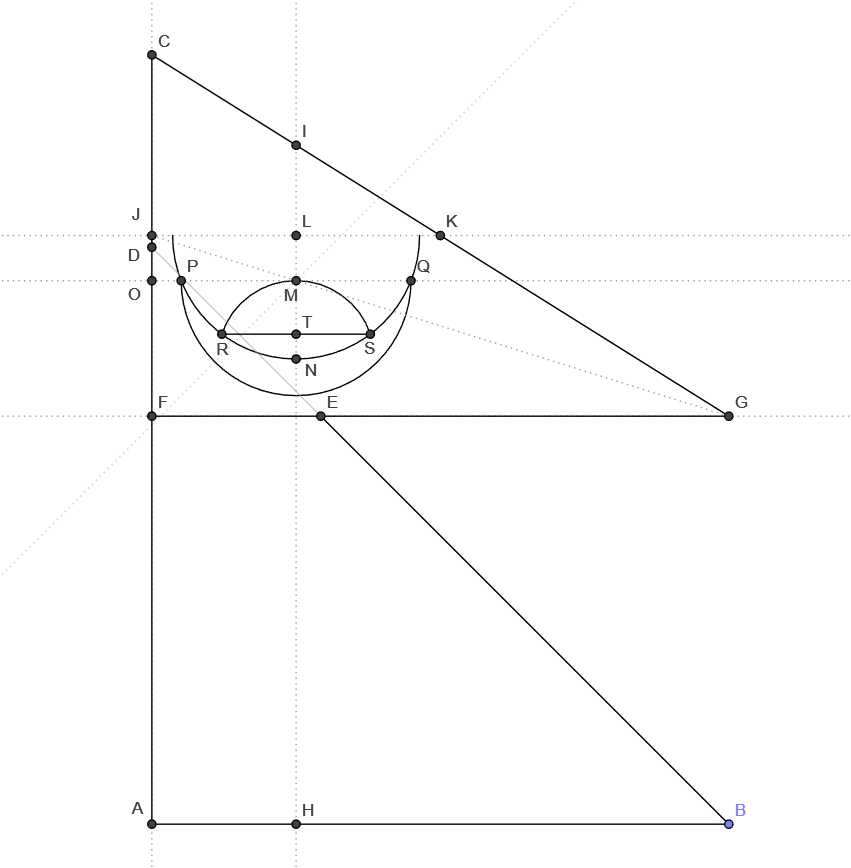

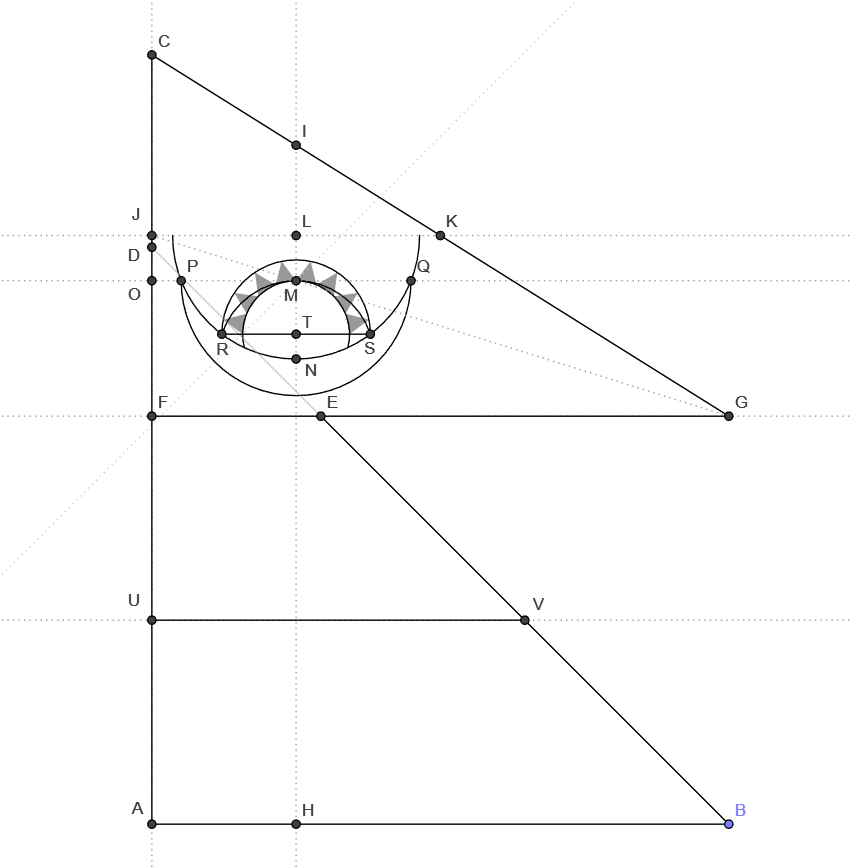

Step 19–22: Constructing the Sun

Below the moon, centered within the lower triangle, shines the radiant sun, a geometric marvel in its own right. The process begins with a careful bisection of AF at U, ensuring precise alignment. A parallel line UV extends to meet BE at V, marking the sun’s foundation.

From a central point W, determined by the intersection of UN and HI, two perfect circles emerge, each drawn with meticulous care to maintain flawless proportion. The outer circle defines the sun’s reach, while the inner boundary shapes its core. Within this radiant sphere, twelve equal triangles burst outward, their tips delicately touching the outer edge.

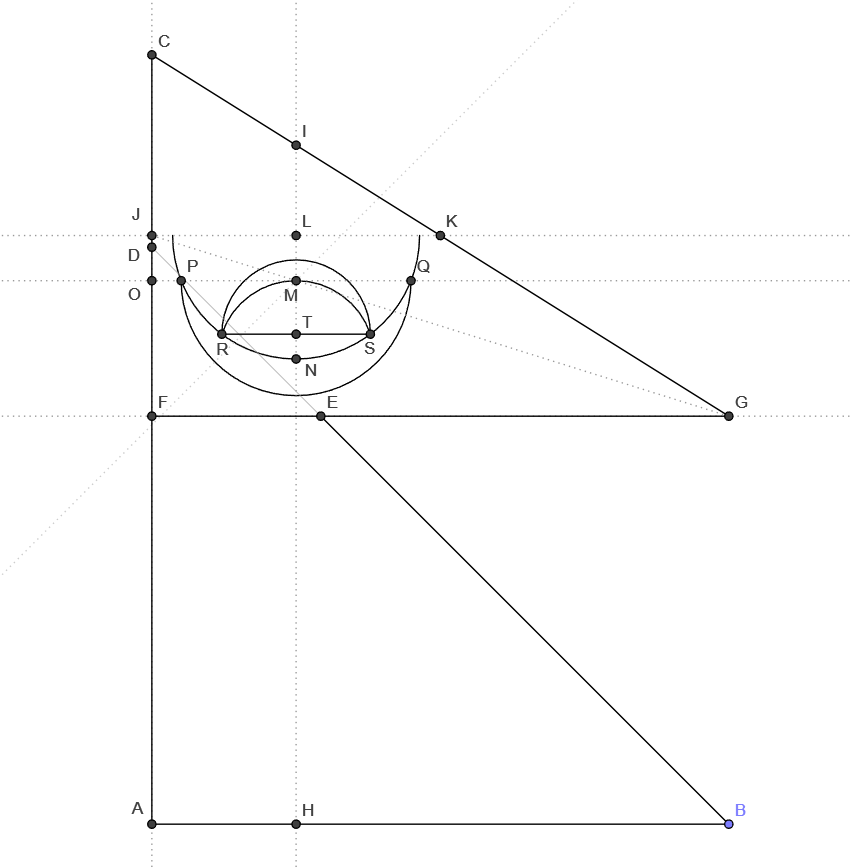

Step 23–25: The Final Border

With the celestial bodies in place, the last step in this geometric construction is the deep blue border, a frame that binds the entire design with both visual and structural unity.

The border’s width is determined by the segment TN, ensuring that the proportions remain consistent.

If the flag is to be hoisted, an additional extension may be made on the side along AC, allowing for the necessary fixtures. With this final touch, the construction is complete, a flag born not of abstract representation but of precision, logic, and national identity.

Fun Fact: Because the slope of the upper triangle is less than the bottom triangle, while creating the blue border, the top triangle extends more to the right than the bottom triangle. It is small, but if you look carefully, you will see it.

Weird Fact: The aspect ratio of Nepal’s flag is unusual. This weirdness comes from the blue border. Without the blue border, just considering the internal crimson triangle, the aspect ratio is 3:4. But with the blue border, the aspect ratio is:

$$ 1 : \frac{6136891429688 - 306253616715\sqrt{2} - (934861968 + 20332617192\sqrt{2}) \sqrt{118 - 48\sqrt{2}}}{4506606337686} $$ which is roughly, $$ \sim 1 : 1.219010337829452184570024869930988566… $$ More on the aspect ratio here.

Reflections on a Flag Unlike Any Other

The Nepalese flag stands unique among nations with its distinctive double-pennant design. Unlike the standardized rectangular flags common today, its geometric shape draws from ancient regional traditions of military and ceremonial banners that have been used in the region for centuries. Its distinctive shape recalls the dhvaja (victory banners) that adorned temples and battlefields since the time of the Mahabharata, where such pennants led armies into righteous battles.

This geometric shape serves as both a national symbol and a monument to the mathematical and artistic achievements of Nepal’s past, connecting its present identity to centuries of cultural development.